Italian Speakers in Australasia

Clare Gervasoni

Italian speaking pioneers arrived in Australia and New Zealand in large numbers from the 1850s. Upon arrival the language, culture and laws were so different to the homeland that most new arrivals were bewilderded. To overcome this disadvantage the Italian speaking community tended to settle together for company, reassurance, but more importantly to assist with the complexities of living and working under an English speaking system. After arriving in Australasia a large number of Italian speakers lost contact with their families in Italy and Switzerland because of illiteracy and isolation. Even those who could read and write in Italian initially had difficulty with English. The great benefit of living in close proximity to other Italian speakers was the ability to communicate with fellow countrymen. The impact of the Italian speaking communities on Australian society is remarkable when considering these humble beginnings.(See A Confusion of Tongues: overcoming language difficulties on the Jim Crow Goldfield in Deeper Leads” New Approaches to Victorian Goldfields History.)

There are many and varied reasons the Northern Italians and Italian speaking Swiss left their country of birth. Including: * Unemployment – closure of the Swiss and Italian border, made it difficult for itinerant workers to find work in Switzerland, or obtain workers from Switzerland;

* Hunger;

* Small properties made it difficult to earn a living from the land, and backward farming techniques and tools increased the problem;

* Political or religious expulsion, including increased taxes in order to pay for the Italian Risorgimento wars which added to the difficulties;

* Fear of conscription. The Austrian invaders of Italy had a system of conscription which involved Contadino from the villages being forced to serve in a foreign army, on foreign soil.

* Crimean war (involved Italy’s Kingdom of Sardenia)

* Word of success of fellow countrymen on the goldfields of America and Australia gave impetus for others to emigrate (chain migration). They sought a quick fortune to “save” their family.

* With the lure of gold as an incentive Swiss shipping companies offered loans to Swiss and Italians to enable them to travel to the Australian Goldfields.

Emigration from Northern Italy Northern Italy was in great turmoil during the 1850s. The fight for Italian unification was raging, there was huge unemployment and great food shortages. During Austrian rule in the late 1840s the Italians were unsettled. The high taxes imposed by the Austrian Government was viewed with great hostility. Often the Austrian invaders were totally ignored by the Northern Italians, who refused to buy or sell Austrian products, or encourage the Austrians in any way. Independence, offered by Italian leaders such as Mazzini, Cavour and Garibaldi, became an important goal. To escape problems, such as agricultural depression and war, many Italians decided to leave their homeland in search of greener pastures in Australia and America.

Emigration from Ticino The Ticinese are ethnic Lombard Italians of Swiss citizenship. Many of the Ticinese were married with families, and intended returning to Ticino after success on the Goldfields. Many Ticinese were trained carpenters of stonemasons because of their traditional jobs in and around Milano, and the rocky contryside in areas such as Biasca.

Emigration from Poschiavo The Poschiavini are ethnic Lombard Italians of Swiss citizenship. Unlike the Ticinese who hoped to find gold then return home, the Poschiavini where willing to work in a mine for as long as it took to earn the necessary funds. They came to Australia primarily to buy land, build a home and become independent farmers.

Arrival in Australia and New Zealand

In the year 2001 Victoria celebrated 150 years since the official discovery of gold. The resulting goldrush after gold was discovered in 1851 saw gold-seekers from all over the world congregate on the Victorian goldfields. Diggers left their country of origin for numerous reasons, with many settling on Victoria’s Central Goldfields. Most were English speaking, but during the mid 1850s ten percent of the Hepburn Springs population spoke Italian. Many of these Italian speakers came from Northern Italy and the Italian Speaking Swiss Canton of Ticino. Today the Victorian town of Hepburn Springs has a population of around 700 people, and is known as the Spa capital of Australia. The population was much larger at the height of Victoria’s goldrush

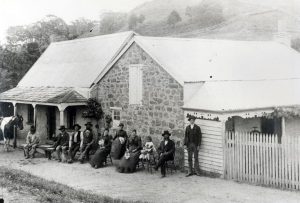

Hepburn Springs, Victoria (formerly Spring Creek on the Jim Crow Goldfields)

The Italian speakers of early Hepburn Springs were escaping political the turmoil of Garibaldi’s wars of Italian independence, huge taxes enforced on the Italians by the ruling Austrians, famine, and a shortage of work due to the closure of the Swiss and Italian border. This resulted in numerous itinerant workers being unable to move across borders to areas offering work. With the lure of gold as an incentive Swiss shipping companies offered a solution making loans available to Swiss and Italians to enable them to travel to the Australian Goldfields.

It is not known why so many Swiss/Italian settlers chose to settle in and around Hepburn Springs. Certainly there are similarities to the Northern Italian and Swiss mountainous regions, and of course language barriers made it important to congregate together. Some Swiss/Italians made their fortune on the goldfields, but the less lucky saw a future in agricultural pursuits, such as wine-making and dairying, as well using other skills such as stone-masonry. Many agricultural and social activities still survive in today’s community, along with many names of Swiss and Italian origin. It is thanks to the Swiss (mainly French speaking from Neuchatel) that we have such a wonderful wine industry in Victoria today. One of the earliest vignerons being Hubert De Castella, an ancestor of marathon runner Robert. Australian Rules footballer Ron Barassi’s family also have their Australian roots in the Swiss and Italian migration of the 1850s.

Mineral Water

Italy is rich in mineral and thermal waters. The word they give spa is terme. Since the Roman times thermal waters and baths became a typical feature of urban life. Since the 1800s hotels with extensive facilities Have grown up around spas, which in turn have received international reputations, attracting millions of visitors each year. In north-eastern Italy many spas have developed on the slopes of the Euganei Hills, which are of volcanic origin. This area features hot water springs, and is known for mud therapy. Abano Terme alone has over 2 million visitors a year, half of whom are from abroad. Another spa region is found in Tuscany, where the high concentration of spas have been in use since the Roman era, including Saturnia, Roselle, Chianciano and Chiusi. The spa resorts in Lazio are linked to the volcanic activity of the region. Of special interest in this region are the waters of Fiuggi which are solely taken as a form of drink. In southern Italy there are numerous spas around the Gulf of Naples. Located in one of the most active volcanic regions of Italy.

Local Swiss and Italian legacies in the Hepburn Springs area include architecture such as the Macaroni Factory (where Australia’s first pasta was made) and Villa Parma; the Italian sausage known locally as Bullboar, with recipes handed down through the generations and known locally as the bullboar (with local families jealously guarding secret family recipes); and who could forget the beautiful Hepburn Mineral Springs? The Hepburn Springs Reserve was set aside in 1865 after being placed in danger due to mining activity. The Swiss and Italians knew the importance of mineral water from their homeland and banded together with the local medical community to ensure the future of the springs at Hepburn. Vincenzo Perini spent many years as caretaker of the Hepburn Springs Reserve, and the Locarno Spring is named after his guest house, which in turn was named after the lake in his native homeland.

The vibrant Spa Country township of Hepburn Springs recognises these special origins during the annual Swiss/Italian Festa and invites visitors to share in the celebration. The area abounds with energy from a rich gold rush history. The Hepburn Springs Swiss/Italian Festa is held annually.

Carlton, Victoria

During the 1920s their was a large migration of Italians into Carlton, a suburb of Melbourne. Many of them were musicians, and introduced Italian food into Melbourne. Carlton’s Lygon Street is known today as the Italian sector of Carlton.

Geelong District, Victoria – A Haven for Swiss Vignerons

It is thanks to the Swiss that we have such a wonderful wine industry today.

Walhalla, Victoria

A number of Northern Italians formed a separate settlement at Poverty Point on the Thompson River somewhere in the 1890s. The rugged steep hills and Valleys around Walhalla obviously was reminiscent to their homeland in the Italian Alps. Many in this Italian settlement were woodcutters, and used environmental building skills while making their homes. Bark huts were built, and in the European tradition hillsides were dug into for shelter and to level the floor. This also enabled the construction of a cellar with easy access into it.

Western Australia

The first count of Italian immigrants in Western Australia was instigated by the Italian Concul General in Melbourne in 1877. Thirteen men were listed, along with their parents names, birthplace, Date of departure from Italy, length of time in WA, rank or profession in Italy, work status, literacy, whether property owned and whether they could speak English. When Victorian gold was more difficult to mine during the 1870s many Italian speakers travelled to Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie in search of the elusive metal.

New Italy, New South Wales

New Italy is near Woodburn in New South Wales. The early Italian settlers, like those around Geelong and at Hepburn Springs, grew grapes and made wine. They attempted a fledgling sericulture industry and played mulberry trees for silkworms to feed on. The New Italy settlers had traditional food of their own, such as salami and cheese. By 1944 the New Italy village no longer existed, but it is remembered through the New Italy Museum.

Greymouth, New Zealand

Hokitika, New Zealand

If you would like to comment or contribute on this article please Email ballaratheritage. Further information on Swiss and Italian settlers in Australasia can be found in Directry and Bibliography of Swiss and Italian Pioneers in Australasia and Bullboar, Macaroni and Mineral Water: Spa Country’s Swiss and Italian Story.